Science for All and All for Science: Road Map to a New Science Literacy

Making a Better World

The Science Literacy Foundation seeks to make a better world by giving the public greater access to the tools and insights of modern science. Traditionally such efforts are lumped together under the rubric of "science literacy," but over the years those words have become associated with a number of outdated or counterproductive concepts. In formulating a path forward for science literacy, then, we begin by redefining the term itself.

Historically, science literacy efforts have been founded on the concept that if people had greater science knowledge, they would be supportive of the scientific consensus and would act accordingly. That perspective overlooks the cultural ties and cognitive shortcuts that are important parts of human behavior, but that also facilitate the spread of misinformation and conspiracy theories. The old view of literacy also promotes a false conception of science as a fixed set of rules and facts rather than an open-ended and self-correcting process of inquiry.

In the SLF view, being scientifically literate means having the cognitive skills for independent, critical thinking; the curiosity required to seek new information; and an understanding of science as a dynamic, pragmatic process that anyone can harness to better their life or their community. In this view, science literacy isn't just something individuals can practice. Groups can practice science literacy collectively to answer questions and solve problems. Science can be harnessed as a force for positive change, especially by those who have been traditionally excluded from or even harmed by scientific work and institutions. In this sense, science offers a critical lens for understanding the past and an optimistic conduit to the future. Science must never become a religion characterized by blind trust, but it does deserve our respect. If we help more people see science as an essential tool in their social and community toolbox and an empowering part of their worldview, we will have done our job.

Over the past year, the need for this kind of transformation has become especially clear. We've all witnessed an unprecedentedly rapid and successful global effort to develop a vaccine against a novel virus. At the same time, vaccine hesitancy and rebellion against public health measures, fueled by disinformation and appeals to personal freedom, have dominated news in the United States through much of the pandemic. As we face the prospect of future outbreaks, the challenge of automation, and the catastrophic effects of global climate change, we urgently need to find better ways to enlist the power of science to address our challenges.

Even small successes could have transformative consequences by tipping election outcomes and shifting public attitudes on important science-related policies. Our ultimate goals are to reduce the cultural and political polarization of public opinion on key scientific topics; guard people against the glut of misinformation and disinformation; and allow anyone to harness scientific thinking to solve individual, local, and community-level problems.

To those ends, SLF wants to train journalists, educators, policymakers, and activists in evidence-based techniques for the effective sharing of scientific information. These ambassadors will help spread the excitement of scientific curiosity, combat misinformation, and show the relevance of scientific insights to individuals and communities.

SLF aims to be:

- A connector, bringing together siloed researchers, journalists, communicators, educators, and policymakers through events, resources, and strategic partnerships so that these groups can work together and learn from one another;

- An incubator, funding seed-level and founder-level projects, providing grants, and forging partnerships that promote creative approaches to science communication, preferably projects at the community level;

- An educator, providing news, tools, guides, and other information for journalists, communicators, activists, and others so they can integrate the most effective techniques of science communications.

SLF's tools will include:

- This White Paper

- A Resource Guide

- An SLF Newsletter

- OpenMind: A digital magazine covering the misinformation crisis

- A series of Summits

- Grants to innovative journalism, news literacy, and communication pilot programs

Although our early projects will focus on science communication, we are optimistic that our efforts in that area will also benefit science education and science policy. We will be looking for partners in these spaces as well. We hope you will join our mission.

Building the New Science Literacy

The Covid-19 pandemic laid bare the deadly consequences of science denialism and science mistrust. Vocal groups of agitators (including government officials) spread misinformation and conspiracy theories about the virus, ridiculed the wearing of masks, and demeaned the doctors and researchers laboring to contain the pandemic. Our nation's sophisticated research infrastructure coexists with large segments of the public who distrust its findings — sometimes because it doesn't fit with their cultural identity, sometimes because of harm done to them by unethical science in the past. Despite unprecedented access to information, many people misunderstand how science is done, leaving them susceptible to appealing falsehoods.

According to the old "deficit model" long embraced by many educators and politicians, poor science literacy is primarily the result of too little exposure to scientific information. In the age of the internet, it is clear the main problem is not a shortage of information but a surplus of confusion, misinformation, and disinformation, much of it disseminated online. The modern media ecosystem bombards people with such a freakish excess of low-quality information and outright deceptions it can be difficult to distinguish truth from bunk. Doubts begin to creep in: Is climate change exaggerated? Is 5G infrastructure dangerous? Do masks really do anything to slow a pandemic? Is Covid itself a hoax?

The United States' current path is self-destructive and unsustainable. The rejection of climate and medical science could make life far worse in the coming years. We need to steer a new course. This new direction will require meaningful, inclusive, and empathetic ways to help people resist the overload of denialism and misinformation while embracing the methods and mind-set of science to improve their lives. And it will involve not just creating better ways to promote scientific understanding, but fundamentally rethinking what science literacy means. That is why a redefinition of terms is central to the SLF mission.

A truly effective science literacy should be relevant across all segments of society, including to those that have been bypassed or harmed by science in the past. It should be without barrier to entry and available to everyone, particularly to people of color and those who are impoverished. It should have comprehensible benefits to people with no formal scientific training. It should show the public how scientific research is actually done while acknowledging the limits of certainty; it should foster the wonder and open curiosity that are innate in all of us; and it should provide an accessible, essential set of principles for analyzing problems and developing workable solutions — in our communities and the world.

Enacting this new approach to science literacy is a tremendous undertaking. Fortunately, we already have a solid foundation to build on. In 2016 a group of innovators in science and science education banded together to produce Science Literacy: Concepts, Contexts, and Consequences, published by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. This report, which established a crucial agenda for future science literacy research, rethinks the old literacy models that emphasized the need for individuals to master a key set of facts produced by a small group of credentialed authorities. Instead, the authors argue that communities can create a collective form of science literacy that helps groups of people achieve shared goals and produce new scientific insights. Their recommendations are rooted in the idea that whole communities can use scientific knowledge together to solve problems and achieve goals.

Other pioneers have been lighting the way as well. The Open Notebook, led by journalist Siri Carpenter, is a nonprofit organization that has been helping science journalists develop their craft so that they can connect with a wider audience. With support from the Science Literacy Foundation, The Open Notebook is piloting a program to mentor reporters in regional media outlets that have limited resources for dedicated science coverage. The goal is to bring thoughtful, informed reporting to the science-news desert — the portions of the United States where people rely on (often struggling) general news outlets instead of the science specialty publications and programs that attract many working science journalists. (A future goal, for us, is having general reporters mentor science journalists so that they are better able to integrate science with the needs of their community.)

The University of Rhode Island's Metcalf Institute is working to shift the traditional paradigm of science communication. SLF is cultivating a partnership with Metcalf's Inclusive SciComm Symposium, which is bringing together science communicators working in wide-ranging settings to help them steer a course toward more inclusion, equity, and intersectionality in their communication and public engagement practices.

The Rita Allen Foundation, established by the late philanthropist Rita Allen Cassel, offers a fellowship to support a culture of civic science in which "broad engagement with science and evidence helps to inform solutions to society's most pressing problems."

Science that starts in the community requires trusted messengers on the ground, and here, too, critical efforts are underway. Although Republicans have resisted working against climate change, for instance, a number of new groups, including RepublicEn, now advocate for the cause with messages and business-oriented messengers constituents can accept. Notable efforts here also include ISeeChange, a nonprofit cultivating community-level organization to crowdsource data and engage potentially skeptical groups on issues like pollution and climate change.

Meanwhile, many Black Americans, keenly aware of historical medical abuse and ongoing racial discrimination in the U.S. health-care system, have been understandably suspicious of the Covid-19 vaccines. They recall all too well that their community members were allowed to progress to devastating end stage without treatment in the secret and unethical U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee. They know that their cells were used, without compensation, to stock government, university, and industrial research labs. They watch with dismay as experimental drugs, including vaccines, are routinely distributed to developing nations where people of color are on the front line to ensure that wealthier groups remain safe. They, too, require messengers who can relate to their experience and acknowledge their fears. This is already happening. Throughout the United States, Black doctors, nurses, and advocates have been sharing their journeys on social media and showing up at hubs to distribute encouragement and vaccines.

The Cultural Cognition Project, led by Dan Kahan at Yale Law School, is helping by conducting groundbreaking investigations into how cultural beliefs shape perceptions of policy and public risk, including on scientific issues like climate change. Critical to implementing all of these ideas are initiatives like the Day One Project. Led by a team of veteran policymakers and scientists, Day One creates actionable federal science policy proposals for leaders on the ground.

The list of innovators in the new science literacy world is far too extensive for us to include in full here. An important part of the mission of the Science Literacy Foundation is to make sure the many groups communicate with one another — across government agencies, nonprofits, educational institutions, academia, and foundations — to share best practices and amplify one another's efforts rather than overlapping or competing for the same resources.

Bringing Science into the World People Know

The unifying factor in all of these efforts is an awareness of how people actually live their lives. Science education is often justified on the ground that science is "useful" to daily life, even for nonscientists. But as researcher Noah Feinstein, an environmental and community sociologist at the University of Wisconsin, has written, there's little actual evidence to support this idea. In reality, people make decisions, take actions, and form worldviews based on many factors, including religion, politics, social pressures, and cultural expectations. Scientific thinking and knowledge may factor into these daily decisions — or not.

In other words, real life is messy. Instead of ignoring this messiness, social scientists need to study it, understand how science can actually be useful in real life, and use that knowledge to shape science education and communication that teaches people to "see how science is or could be significant to the things [they] care about most," according to Feinstein. The act of "making science relevant" to daily life is something people can learn to do and get better at with practice, he notes.

Communicating science literacy in a way that is personal and useful demands that we meet all people in their comfort zones (at places of worship; in Facebook groups; in community organizations, barbershops, and supermarkets), not just in museums and schools. We also must encourage engagement with scientific issues that are relevant to people without challenging their core values or religious beliefs. In this context, science literacy occurs when consideration of scientific issues becomes a normal part of the personal and civic decision-making process that people everywhere employ to improve their communities and lives. It flourishes, too, when people are exposed to science as a joyous process of curiosity and discovery that is compatible with many different worldviews.

Scientists, educators, government officials, and journalists alike must recognize that hesitancy and apprehension toward a host of science-related issues vary significantly from one group to the next. It follows that the efforts to reach these groups must be equally varied, and also respectful and inclusive of the cultures involved. That said, a shared culture of science, based on curiosity and personal benefit, can connect these disparate groups.

To succeed in this fresh approach to science literacy, SLF will enlist a wide range of natural allies. For science journalists and science communicators, the task requires reaching into the science news desert plaguing rural communities, places where people are often distrustful of institutions and detached from top media outlets. Individuals in these communities may get much of their information from talk radio, local TV news, or social media, all platforms we plan to penetrate to fight misinformation.

For science educators, the goal is to emphasize big ideas, problem solving, and investigative techniques over an accumulation of narrow facts while training students how to vet and question science news. These skills are more complicated to teach than the prevailing model of fact-and-formula memorization plus standardized testing. But educators report this kind of learning is more meaningful, leading to longer-lasting skills in logical and open-minded thinking, both of which are crucial to seeing through misinformation and dishonest, emotional arguments.

For scientists themselves, there is a pressing need for more members of the research community to speak with the public in a clear, culturally relevant voice. Universities and institutions rarely offer incentives for their scientists to make media appearances or to engage with the public on social media, or even recognize the effort. Some even discourage it. The scientists who are skilled at communication should be encouraged to do so; even a modest effort in this area could have a significant impact. One solution SLF is considering is a media certificate to validate the work of scientists involved in outreach.

Within and across all the groups involved in promoting science literacy, diversity is an absolute must. We need individuals from many different backgrounds leading the way, so that our nation can address the needs of various communities and reach them with a persuasive, trusted voice. Only by approaching communities in new ways, or even creating new communities that coalesce in shared interest, can we overcome the human penchant for silos, sectarianism, and in-group loyalties, the tendency to follow customs and beliefs even when they run counter to self-interest or common sense.

That awareness of shared interest is crucial. Without a system of critical analysis informed by science, we leave ourselves vulnerable to future waves of pandemic illness; a planet altered by sinking cities and rising seas; an onslaught of floods, drought, and superstorms; sickening air pollution; increasing food insecurity; and racism encoded into our laws and our technologies. Undue anxiety about vaccines and 5G radiation are leading to political radicalization. Conversely, political polarization over the risks of climate change and environmental toxins has fostered indifference or resistance to policies that would increase the safety of the public, even among groups that would directly benefit from those policies. Black and Indigenous people and other people of color are already disproportionately vulnerable to every single one of these enumerated disasters; the stakes have long been high for them, and science hasn't served these populations. We must change that now.

Cultivating a mind-set that includes critical analysis of science is crucial to our survival, and it can be achieved, but not in the ways we've relied on in the past. For instance, research has shown that fact-checking doesn't change people's minds. But we don't need to change every mind to move the needle far enough to shift policy in the United States.

If we can reach even 5 percent of the public, especially those not paying attention or already on neutral ground, that would help a greater number of us defend against manipulated science news. Just look at what a 5 percent shift in the vote would have done in recent American elections, at all levels of government. If we can move the science literacy needle even that little bit, it would radically shift science policy in the United States, brightening our prospects and lifting our civic lives.

Learning from the Mistakes of the Past

Fostering a new science literacy requires an honest assessment of the deep historical roots of anti-scientific attitudes. The rise of scientific institutions in Western countries went hand in hand with the Industrial Revolution. Western science led to remarkable intellectual advances and tremendous improvements in the standard of living, but it also enabled colonialism and the wholesale destruction of non-Western societies. We must confront this complicated history directly. We need to learn how to maximize the ways science can improve people's lives while addressing the ways it has been abused in the past — abuses that are still regularly cited by anti-science agitators.

Here in the United States, science became the dominant social value during and after World War II. In the first half of the 20th century, the influential philosopher and science proponent John Dewey charged that scientists were remote and elitist and used language unrelatable to the public as a whole. Dewey believed profoundly in the central value of science but thought it should be taught as part of a broader initiative focusing on critical thinking. He wanted the young to truly grasp science as a mind-set and railed against the wholesale (mindless) cramming of scientific information into children's heads at school.

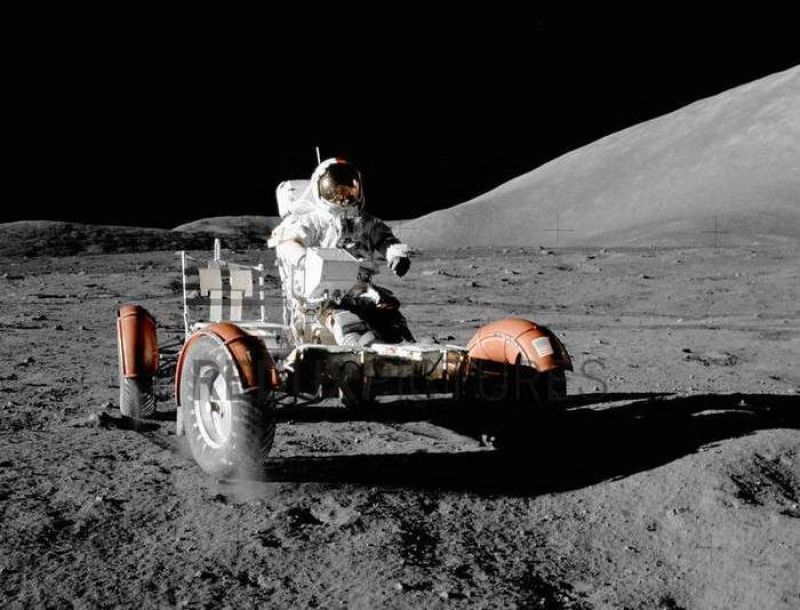

Dewey's impulse to humanize science was eclipsed by the urgent needs of World War II, when rapid technological advances in radar and atomic weapons propelled the Allies to victory. With technical prowess so important, science education was often approached as a means to achieve the practical goal of creating a scientifically adept workforce of people technically trained and ready to step into the breach. Even before the war ended, Vannevar Bush, who had overseen most of the United States' military R&D, began contemplating a peacetime version of that wartime approach. In "Science, the Endless Frontier," a now-famous report delivered to President Harry S. Truman in July 1945, Bush argued that science was key to the future economic prosperity, national security, and global leadership of the United States.

Bush's pragmatic mind-set helped guide the establishment of the National Science Foundation (NSF) in 1950 and the rapid growth in federal funding of science that followed. The trend accelerated in 1958 after the USSR's success with Sputnik, when experts like Stanford professor Paul Hurd argued that the United States had to intensify its science efforts to have a prayer of triumphing in the Cold War. But even through much of the space race, a majority of Americans did not support going to the Moon; they were more concerned with economic worries, pollution, and social unrest.

Over the next few decades, the term science literacy caught on, and researchers developed tools to quantify it. In a 1979 survey for the NSF, University of Michigan research scientist Jon D. Miller asked participants about basic science facts (such as whether Earth revolves around the Sun). He concluded that Americans knew little about science, a perceived inadequacy that educators tried to correct by standardizing science education. As we now recognize, this approach led to more testing and memorization rather than comprehension, along with a failure to consider the many cultural, racial, and gender assumptions implicit in the seemingly objective information being taught (and the way that information was taught and tested).

Journalists and media outlets struggled mightily to improve public understanding of key science issues, often guided by the same mistaken notion that information equals understanding. But no matter how much knowledge they tried to impart, or how much narrative storytelling or splashy art they wrapped it in, the public grasp of actual science knowledge (at least as it was officially measured) remained skewed toward college graduates, those with technical backgrounds, and others already engaged with scientific issues.

From the explosion of newspaper science sections and science magazines in the 1980s to the emergence of today's Vox-style "explainers," literary-science websites like Aeon and Quanta, and slick science festivals and Ted Talks, there has been an abundance of exceptional science journalism and programming mostly reaching the same audience over and over. By and large, all of that lovingly produced content is styled in ways that don't reach the disenfranchised groups that could benefit most from a better understanding of science, including people of color, immigrants, the LGBTQ+ community, and people with disabilities or chronic illness. These boutique media outlets often target people who are already stakeholders or enthusiasts without impacting the rest of the world much at all.

British researcher Brian Wynne, who first described the information-deficit model of science literacy back in the 1980s, has since called it an incomplete solution at best, a fallacy at worst. In one survey, just 50 percent of the public knew that antibiotics kill only bacteria and not viruses, and 46 percent knew that electrons are smaller than atoms. And less than half agreed that humans descended from other animals that came before. Such headline-grabbing statistics capture little of the public's actual scientific understanding and attitudes, however. In other surveys, some groups with high fact-based science literacy scores also refuse to accept consensus ideas in science.

Old habits die hard, though. Information-driven education was said to be effective at filling science and technology jobs, it was easy to measure on standardized tests, and speaking to an audience like themselves is a natural mode for journalists who mostly come out of a white-dominated academic background. Even as pioneers forge a new way forward, the past lingers, feeding some segments of the population a feast of scientific discoveries and insights while other parts starve.

Activating the Love of Science

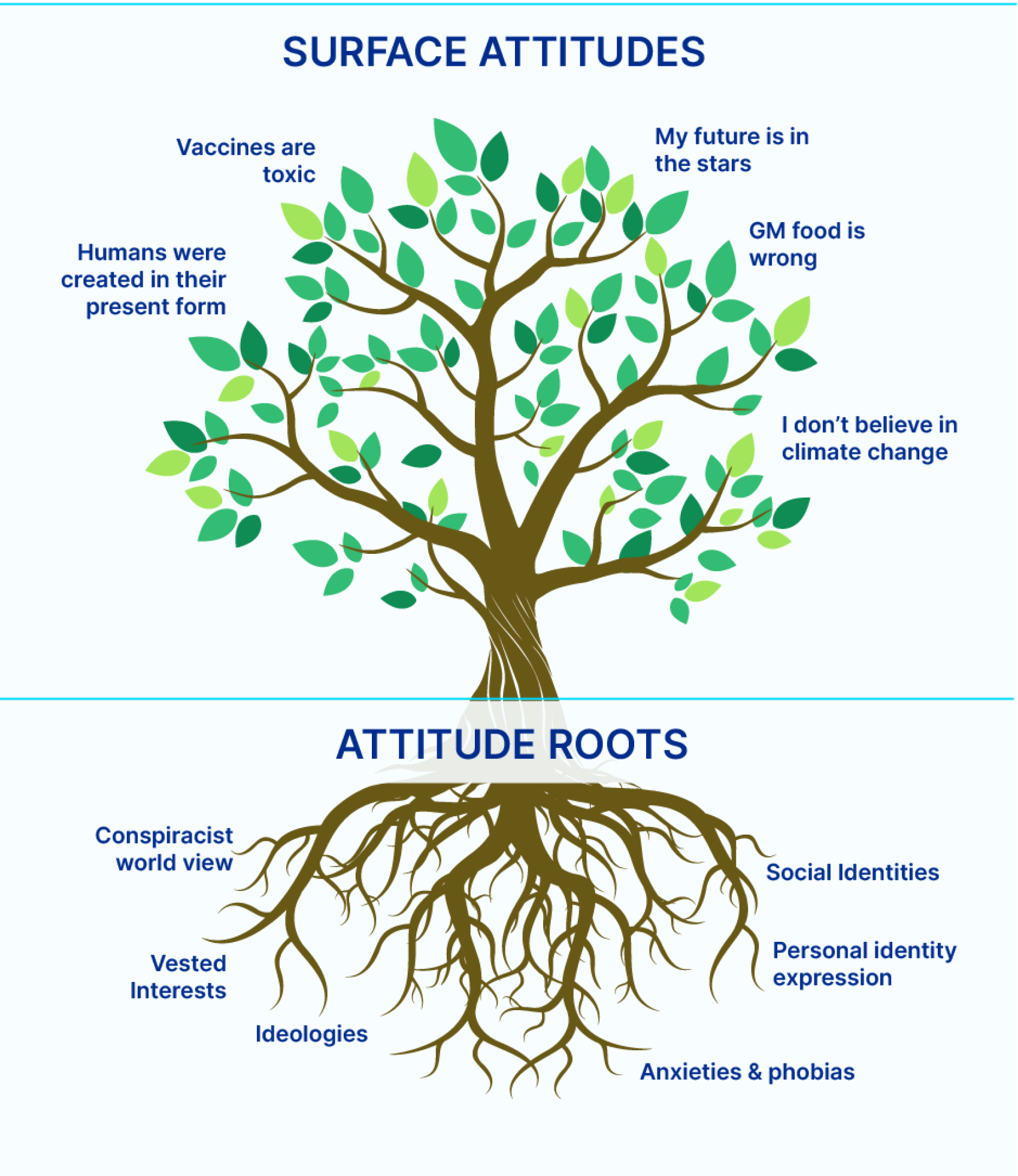

Understanding how to break free of those habits requires looking at the roots of misinformation, from lack of access to accurate information to the willful embrace of denialism and conspiracy theories.

Contrary to popular belief, Americans are not averse to science as a whole, and science denialism is not concentrated among those with low levels of education. A 2020 Pew survey shows that more than 80 percent of Americans have a positive view of science and trust that scientists generally act in the public interest — notably higher than the numbers for religious leaders (57 percent), business leaders (46 percent), or elected officials (35 percent). That number declines, however, as soon as the focus shifts to emotionally and politically charged topics such as climate change, vaccination, or gene therapy. When values, including political and religious beliefs, enter the equation, people with the highest level of education and the most access to information are actually the most polarized along political or religious lines.

Drawing on extensive survey data, Yale's Dan Kahan has found that people tend to endorse "whatever position reinforces their connection" to the community around them, a tendency many trace back to our days as hunter-gatherers. These alliances were critical to physical or social survival. "The same groups who disagree on 'cultural issues' — abortion, same-sex marriage and school prayer — also disagree on whether climate change is real and on whether underground disposal of nuclear waste is safe," wrote Kahan in Nature in 2010. The only way to subvert these tendencies and make people more open-minded to scientific evidence is to communicate with each group in a way that feels meaningful and relevant to it, a subtlety that journalists often overlook.

The Yale Program on Climate Change Communication has conducted more than 10 years of polling on public attitudes toward climate change. From those surveys the researchers identified "global warming's six Americas,", groups with responses ranging from dismissive to alarmed, though of course most of us are gathered in a common ground and not at either extreme. A 2016 Pew study similarly shows wildly disparate climate attitudes among different portions of the public, especially along political lines.

A separate 2019 Pew survey drives the point home. It reveals that what Americans know about science varies dramatically by education, race, and ethnicity; at the same time, according to survey author Cary Funk writing in Scientific American, "people's beliefs about many science-related issues are not connected with their levels of science knowledge." Well-educated environmentalists may sympathize with dubious arguments against genetically modified crops, for example. Studies show that people who oppose vaccines hail from both the left side of politics and the right, though they typically voice different reasons for opposition. Each issue and each separate "public" poses science literacy challenges of its own.

The bottom line: When it comes to science literacy, people from all walks of life can be challenged by lack of access to information or a siloed culture they dare not buck. But these populations can be reached and enabled if they come to view science as a boon to their lives.

Making Science an Ally of Freedom

The cultural obstacles to science literacy are exacerbated in the United States by a national ethic of personal freedom that rebels against authority, particularly with respect to the environment or health. That ethic helps explain the eclectic political identities of vaccine skeptics. "It's not that [they] distrust science in totality," explains medicine and culture scholar Bernice Hausman of the Penn State Cancer Institute in an essay for Aeon. Rather, she says, these groups, both right and left, don't want the government or large corporations telling them how to lead a healthy life.

Kahan's research verifies that conclusion: Simply exposing people to more scientific information cannot overcome mistrust or denialism connected to group identity, including religion, class, and political affiliation, or to years of institutional abuse. The primal value of freedom only intensifies that resistance. When scientific findings clash with group identity, many people's first reaction is to side with their peers, even in the face of well-supported evidence. In such instances, simply leveling with people, honestly, might be the best way to break through.

For a long time, the cultural forces of anti-science were held in check by a mass media dominated by three television networks, a handful of major newspapers, and local papers with their own expert, well-trained reporters. In today's hollowed-out media landscape, many outlets (especially resource-constrained local TV, newspapers, and websites) are unable to cover the uncertainties and shifting hypotheses that characterize the scientific process.

At the same time, people now have easy access to a dizzying array of fringe websites and online communities, ranging from Reddit to 4chan to innumerable Facebook groups and YouTube channels. Clickbait sites crank out stories with maximal emotional impact — stories that often abound with misinformation — because they reliably drive traffic and generate revenue. In all these ways, groups with deliberate political agendas or perverse economic incentives can easily exploit modern media to spread deceptions in psychologically persuasive formats. They can also spread a mistrust of scientists and experts, pushing their skepticism to reach new audiences.

Covid-19 has highlighted the consequences with ghastly clarity. Polling has shown that 70 percent to 90 percent of Americans say they regularly wear masks—a number that actually increased over the course of the pandemic. Nevertheless, a significant minority of people contend that masks are tools of oppression that fan the flames of disease.

Skeptical attitudes toward vaccines, meanwhile, can be couched in the language of personal freedom — or based on the very real fear that a community will become a guinea pig, vaccinated first to protect a wealthier group — in the same way a royal food taster risks being poisoned to protect the king. The science around the pandemic is now perceived in such personal and political ways that individuals routinely rebel against their own interests. A mere "fact-check" from CNN won't be sufficient to turn things around.

It would be extremely challenging to weed out every conspiracy theory or manipulative website; healing centuries of betrayal will take time. But what we can do is help a cross-section of people evaluate science stories within a supportive and meaningful framework. We can bring better science coverage to local media outlets and communicate with distinct groups through trusted messengers. Inspiring a sense of curiosity, meanwhile, would go a long way toward helping people grasp how science actually works.

As with misinformation, small inputs are meaningful here. Given how powerful the appeal to freedom has been in encouraging people to defy Covid-19 safety measures or refute vaccine science, even a slight reframing of science as an ally of freedom and personal well-being could potentially shift news coverage and election outcomes, with dramatic effect.

Recognizing the Importance of Diversity

Current science communication efforts tend to benefit specific audiences — the affluent, college-educated, and non-disabled, write inclusive science communication leaders in a January 2020 article. Making science communication more impactful necessarily involves listening to, learning from, and championing the voices of the "historically marginalized and minoritized individuals and communities" who have been "largely overlooked and undervalued" in past science communication efforts. How journalists, scientists, educators, and others communicate about science can either invite individuals and communities to be more involved in the world of science or shut them out and perpetuate existing inequities, explain the authors of the 2020 "State of Inclusive Science Communication" report.

We won't succeed if we don't work relentlessly to make the fields of science journalism, science education, science policy, and scientific research more diverse, equitable, and inclusive. Our colleague Alberto Roca, as executive director of the nonprofit DiverseScholar, is promoting the recruitment and mentoring of postdocs of color, helping to raise their academic profiles and, as part of professional development, coaxing more of them into science communication. This represents one strategy of many dozens of groups working to increase representation for women, Black and Indigenous people and other people of color, the LGBTQ+ community, and other underrepresented groups. The National Association of Science Writers, for instance, launched diversity fellowships to make it easier for students from all backgrounds to participate in low-paying internships that are often crucial to breaking into the science journalism field.

Lack of diversity among scientists and science communicators has long been a challenge in reaching disengaged or science-starved communities. Even after level of education, attitudes toward science, and socioeconomic factors are accounted for, white Americans still score higher on science literacy measures than Black or Hispanic Americans, according to a 2018 analysis published in Science magazine. The article's authors — including Nick Allum, a quantitative social scientist at the University of Essex in England and Louis Gomez, a social scientist at UCLA — hypothesize that the disparity could be due to systemic differences between what people experience in the education process, including factors like microaggressions and stereotype threat. They recommend evaluating measurements of education quality to assess how well they work for different groups of students, along with training campaigns to help scientists, teachers, and employers be more sensitive to the subtle manifestations of bias.

Others add that historical medical mistreatment plays a role as well. In short, disparities and attitudes alike can be traced to who has actually benefited from science, and at whose expense science has advanced. Let us be clear: Racism and sexism run deep in the history of institutional science. Merely acknowledging a lack of diversity lends credibility to the thinking that science is accidentally nearly devoid of Black/brown/female/queer folks. It is not. The system was created to be exclusionary, and only aggressive intervention will set it right. At SLF, we'll be on the front lines of that fight.

Fortunately, the emerging field of inclusive science communications (ISC) already has strong champions. The Metcalf Institute has started a biannual Inclusive SciComm Symposium and has begun publishing research literature to define the field, which is nascent but growing. SLF is committed to providing these pioneers with the support they need to further the mission of creating and perpetuating a powerful new approach to science communications.

Addressing science suspicion in conservative or Republican communities requires its own form of outreach. Over the past few years, and especially during the Covid-19 pandemic, public trust in science has increased overall in the United States, according to the 2020 Pew study. Almost all of that increase has occurred among Democrats, however. Improving science understanding in heavily Republican areas of the country will inevitably require finding common ground with conservatives and libertarians who embrace scientific evidence and science-based solutions, at least on specific issues. The aforementioned RepublicEn, an environmental activist group founded on the principle that "the power of American free enterprise and innovation" will "solve climate change," demonstrates one of the alternative approaches to science communication.

Across all groups, experts recommend deploying trusted messengers who might position information in a way that communities will accept. The 51 Percent Project, a climate-change communication effort out of Boston University, enshrines this as one of its core principles. The project identifies a broad range of people who can act as those messengers: kids; scientists; health-care professionals; faith leaders; broadcast meteorologists; staff at zoos, aquariums, museums, and nature centers; university leaders; farmers; celebrities; business leaders; top athletes; best-selling authors; musicians; news anchors; and late-night comedians. The Science Literacy Foundation is partnering with leaders in community-based science-outreach organizations to help more of those messengers, drawn from myriad cultural communities, to engage with public audiences.

Crafting New Strategies for Science Literacy

We have identified a number of broad strategies for a new type of science literacy effort, one that takes into account the realities of the culture and the media structure.

Be transparent about how science really works. One simple corrective is to promote a wide understanding of how science is done. Most students are still taught about science as a set of rigid methods that yield incontrovertible truths rather than an iterative, imperfect, and flexible process of discovery that makes mistakes and then corrects itself over time. "I think the American public does not have a clear understanding of the scientific process," Dominique Brossard, a science communications expert at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. "And the pandemic is a good example of that." Universal acceptance of social distancing and mask-wearing, for instance, could have drastically reduced the Covid-19 death toll in the United States, according to multiple studies.

Misunderstanding the scientific process causes people to lose faith when new information contradicts the old. Community and so-called citizen science projects, which offer amateurs an opportunity to work on research projects that require only limited training, could be an important tool here. (Despite the commonly used name, one definitely does not need to be a "citizen" to participate.) More than a quarter of all Americans report that they have participated in a community or personal science activity at some point. These projects not only give people direct experience with scientific methods but also have created a diverse community that could be enlisted as educators in schools and museums or as ambassadors to culturally affiliated groups online or in real life.

Encourage scientific curiosity. As Kahan has pointed out, curiosity about science promotes deeper immersion and greater understanding overall. Curiosity fosters problem solving, critical thinking, and an independent mind-set that can help people evaluate scientific information for themselves, rather than rely on untrustworthy intermediaries. Fortunately, promoting curiosity can be accomplished in myriad creative ways — via science publications, podcasts, museums, science centers, and much more.

Help people understand how the mind works. Recent studies show that presentation and familiarity can be more important than information in understanding new things. From sharp colors to clear fonts to simple sentences, whatever makes something easy to understand also makes it seem more credible, according to Norbert Schwarz, a cognitive psychologist at the University of Southern California. Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter are effective at spreading misinformation in part because they endow it with the appearance of truth: News comes in simple, repeated bites, typically delivered by friends who seem trustworthy. Once the brain codes something as true (or false), it's hard to shake the bias, even if new information shows you should.

Cognitive researchers have identified a number of effective practices for combating misinformation through science journalism and communication: Never begin a story with a falsehood, even to debunk it, since the first statement will stick in people's minds. Anticipate likely misconceptions when reporting stories. Debunk falsehoods as soon as they appear, before they receive much media play. Many experts recommend "prebunking" — literally listening for myths and conspiracy theories just starting up and inoculating the public against them by attacking them, head-on in stand-alone stories, posts, and tweets.

Promote digital literacy, an understanding of the subtle, often pernicious ways that the internet and social media affect the way we respond to information. For instance, research shows that nasty responses to a neutral story online can influence how people engage with the information, sometimes in politically polarizing ways. Also important: When people search online, they must be able to defend themselves against deceptive stories and videos that can provoke rapid, unconscious emotional responses. We can inoculate people against online misinformation by making them aware of these manipulations and, if possible, widely presenting the correct information to the public first. We can also give people easier access to valid information presented in accessible and personally relevant ways —for instance, through widely read tweets or stories on cable news.

Make people aware of their unconscious biases. When it comes to the charged issues causing us so much trouble, people take mental shortcuts that bypass their knowledge. These shortcuts are social, moral, ethical, and psychological. Sometimes they are so unconscious and symbolic that they can be hard to discern, says Brossard. People may be able to make more constructive, science-informed decisions when they step back and consciously consider those hidden cognitive influencers that make them react a certain way no matter how much they know. This is a teachable skill that can be incorporated into citizen science and grassroots science outreach by trusted messengers and organizations.

Foster communities of culturally connected, science-engaged people. Knowledgeable teachers, parents, patients, and hobbyists, among other interested community members and leaders, are often best equipped to bring science into the public sphere. That's what sociologist Noah Feinstein, Brossard's colleague at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, discovered while interviewing parents of autistic children. Parents didn't always think of their problems in scientific terms, but they sometimes relied on a web of resources, including other parents, online research, scientific experts, and "near-science" experts, like behavioral therapists, to navigate problems with their child. Whether or not these parents started out engaged with scientific experts and sources, when they joined together to share resources, research, and ideas, often online, solutions emerged.

Focus on local, tangible issues that build trust and inspire personal investment. We need to deliver the science related to problems or issues that people can unite around to solve, no matter what their politics, says Allum at the University of Essex. For instance, coastal residents in Florida are largely Republican, but political talking points about climate change become irrelevant to them when their own homes are at risk. Following this approach, the University of Colorado at Boulder established the Water Desk, a journalism project to foster science reporting focused on water issues of interest to communities around the Colorado River Basin.

Address each audience on its own cultural terms. No matter how fine the reporting may be in outlets like The Atlantic or the New York Times' Science Section, large portions of the American population will never pay attention to these stories. Many people say they are simply too busy to pay more attention to science news; others may view these outlets as liberal, biased, and elitist — or literally inaccessible, behind a firewall they cannot afford to remove. That's why so much science news coverage never reaches beyond a core audience, and why well-intentioned efforts to reach outside that audience often fail.

When talking to people with different worldviews, particularly those who actively resist scientific knowledge, know what you're up against, advises Stephan Lewandowsky, chair of cognitive psychology at the School of Psychological Science at the University of Bristol in England. Science information is seen as more credible when it comes from trusted members of a particular community. If outsiders want to speak to the community, they should learn their audience first. Ultimately the goal is to empower a host of trusted messengers, from clergy to librarians to teachers, who work with the community each day.

Putting Ideas into Action

The Science Literacy Foundation is committed to investigating the challenges of science communication and sparking immediate, tangible, scalable change. One problem is a shortage of funding for the study of what really works to promote science literacy. Another problem is a fragmented effort, scattered across many agencies and programs. We therefore came together to facilitate like-minded colleagues, helping them find one another and helping them amplify their efforts. We are supporting symposiums and panels where synergy can occur. We are also working with partners on potentially transformative projects to break through the obstacles that have long impeded progress in addressing science literacy in the United States.

Our flagstone project will be the editorially independent digital magazine OpenMind, which will focus on confronting the misinformation crisis. The publication will be a forum for fresh, honest, and thoughtful investigations into the world of science communication, misinformation, and disinformation. We will dig into the cultural, political, social, and psychological obstacles that are holding back science, including those from within the scientific community itself. Our target audience is everyone with a stake in the solutions — which is to say, everyone.

We have also identified a number of policy initiatives that we believe are critical to the implementation of the new science literacy. Some of these are projects that SLF has already begun to tackle through OpenMind and strategic partnerships.

Watering the Science News Desert

Although many Americans say they are interested in science news, only 36 percent report that they encounter science news regularly and just 17 percent actively seek it out, according to a 2017 survey from the Pew Research Center. Meanwhile, local journalism is withering, with more than 1,800 local papers closing since 2004, turning many parts of the country into news deserts.

To address these issues, the Science Literacy Foundation has funded a mentorship program created with The Open Notebook to partner experienced science journalists with non-specialist reporters and editors, particularly those who work for local news outlets. The goal is to improve the coverage of science at those outlets by providing local reporters with the knowledge and guidance to write confidently about science. The pilot program will investigate the needs of general-interest reporters and find ways to fulfill them so that they can cover science stories more confidently and accurately in ways that are appropriate for their audiences.

Unleashing the Power of Science Journalists

There are thousands of professional science writers and communicators in the United States. They are already trained to understand the practices and findings of science, turn them into compelling stories, and bring them to the wider world. "They know how to follow the money, how to report on the power structure of science, and how people work the system," Feinstein says. Still, even veteran journalists regularly fall prey to common errors that spread misinformation, from inadequate vetting of sources to both-sides reporting to audience pandering to leading with myths before debunking them.

SLF is curating a resource guide that provides both veteran and early-career journalists with resources for reporting on science effectively. The in-house digital magazine, OpenMind, will also be a platform to unleash the creativity and power of science journalists to confront misinformation, conspiracy theories, controversies in science and science media, and more.

Connecting the Public with Science and Scientists

A cornerstone of SLF's work will be providing small grants to scalable pilot projects that target local and unique science communications efforts. Projects that are awarded funding will focus on communities, especially underserved communities, and will be designed for scalability and to attract future funding. Further, they will aim to improve science news literacy; combat misinformation and disinformation; or engage people on high-impact scientific topics like climate change, vaccines, and nutrition.

Fighting Misinformation with Cognitive Science

Psychology and social science research have inspired innovative, data-driven ideas about how to address the chronic problems of misinformation and exclusionary styles of science communication. We believe that these areas of research require more support. SLF is exploring partnerships and grants to advance knowledge in this field, focusing on under-studied questions about the ways that misinformation takes hold in the popular mind.

Opening Dialogues on Hot-Button Science Topics

To tackle challenging, complicated science topics, we recommend expanding the use of trusted messengers to reach across the political and cultural divides on key issues like climate change, vaccination, and genetic engineering. For instance, original reporting projects could explore better ways to talk about science-based controversies and cover efforts by journalists and communicators to change the way they engage with readers about hot-button science topics.

Addressing Disparities

Unfortunately, much of what we know about the efficacy of trusted messengers comes from anecdotal evidence. There is still too little authoritative research into ways to build science trust and literacy systematically across different racial and ethnic groups, including strategies for engaging on various science topics one audience at a time. This is another area that deserves more research support. Targeted grants and partnerships could enable researchers to investigate open questions such as the psychology of the microaggressions and closed environments that alienate people of color from the world of science.

Building Trust

One clear priority for the new science literacy is improving trust in the medical system and in scientific institutions across all populations. That will be a steep hill to climb. We look to reporting from our colleague Julia Craven of Slate in a 2021 piece about mistrust of medicine in Black communities. Suffering a swollen arm and painful cyst, she'd seen an ER doctor, who prescribed antibiotics. When the swelling continued, she returned to the ER to discover the antibiotic dose she'd been given had been too low, putting her at risk for sepsis.

"The realization that I'd been facing such negligence and disregard for my well-being changed my whole sense of what to expect, and what to fear, from the medical establishment," Craven writes. "My new distrust bled over into nearly every interaction I'd have with a doctor afterward — and it colored my feelings about whether or not I would want to receive the vaccine for the novel coronavirus." Abundant statistics back up this anecdote. We, as a society, need to do better.

A Closing Thought

By empowering more people to care and think deeply about science without violating their values, we will help them make better decisions for themselves, their communities, and our planet as a whole. We are at a crossroads right now: We can either act to change course by fighting for science, or we can passively watch climate change, pandemics, environmental injustice, and other dangers cause widespread suffering and hardship.

There is no Plan B for us, and no Planet B — nowhere for humanity to escape from the problems we face. We must act now, with intelligence, honesty, clarity, and compassion. Despite the challenges, we are optimistic and positive that together we can push the needle forward and change our course for the better.

Opening Image Credit: Marco De Swart/Getty Images